Exploring C++ Inheritance (1 of 2)

17 May 2013 - CPP, Visual Studio

Introduction

Quite a while ago - still working with Rarebyte - I was designing a class library for game related stuff. Naively ensured that OOP was the only real solution to scaling software, we did a lot of (multiple) inheritance and packed stuff into the library, most of what we never needed anyhow. At one point the question came up on how this was implemented and if we actually knew what this (multiple inheritance especially) meant to the data structures. With self-competence I garbled something about function pointers and tables and a hidden pointer in every object etc. What it meant exactly, I didn't know.

It did not really bother me for a long time either. Only when I discovered that C style casting in C++ can cause the value of a pointer to change, I got nervous. I had always thought that casts where pure pointer-value reinterpretations, but hours of debugging a related problem taught me something else.

In the back of my head, I always knew that at some point I would write the C-equivalent of an inheritance chain in C++, and last night I actually did that.

C++ Version

Let’s first consider a simple inheritance chain in C++: A base class named Base and a class derived from Base called Derived. Base has a single integer named “datamember” as well as a virtual function print that spits out its information to the standard output. Base has a constructor taking the “datamember” value as an argument.

The derived class has a second data member named “derivedMember” (for the sake of simplicity also an integer), a constructor taking both data members, the value for “derivedMember” as well as the value for the Base constructor and another virtual method, called “readFromFile”. This is to demonstrate how derived classes can further extend the number of virtual functions of a base class.

class Base

{

int baseMember;

public:

Base(int baseMember);

virtual ~Base();

int getBaseMember() const;

virtual void print();

};

class Derived : public Base

{

public:

int derivedMember;

Derived(int derivedMember, int baseMember);

virtual ~Derived();

virtual void print();

virtual void readFromFile();

};To test the code I have a simple main method constructing a Derived as well as a Base instance on the stack and passing it as an reference to a function, which in turn calls the print method of the object passed in (which is of type Base). This is a virtual function call and therefore dereferences the function pointer pointing to the function pointer table along with an index to the number of the function we are calling. Since function pointers are always of a concrete size (4 or 8 bytes, depending on architecture) the address of the function is calculated using vtable pointer + functionnumber * sizeof(functionpointer).

void PrintObject(Base &ptrBase)

{

ptrBase.print();

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

Base base(10);

Derived derived(10, 20);

PrintObject(base);

PrintObject(derived);

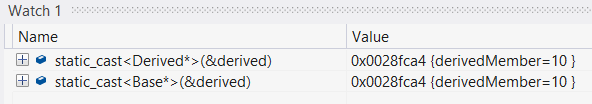

}Stepping through the code using Visual Studio, we can see that the addresses to the Base object either as a Base pointer or as a Derived pointer object identical, which is something we expected anyhow, since at the end of the day an instance of Derived is a Base.

Let’s take a look at why this seems somewhat special:

C Version

Consider what the C equivalent would look like. I'm not a compiler builder so there are probably many tricks that could be applied, but the basic structure is the following:

In order to maximize code reuse, I structured it, such that a class is represented by multiple structures. One for the function pointer table and one for the data members. For every class there is always a single instance of the pointer table and instances of the class have a pointer to the single (global) instance, which we refer to as the virtual function pointer table.

typedef struct Base_t Base;

typedef struct BaseTable_t

{

void (*print)(Base* _this);

} BaseTable;

typedef struct BaseData_t

{

int baseMember;

} BaseData;

typedef struct Base_t

{

BaseTable *vfptr;

BaseData data;

} Base;

void BaseConstruct(Base *_this, int baseMember);

void BaseDestroy(Base *_this);

The base class structure therefore consists of a pointer to a table structure as well as a structure containing all data members of the base class (a single integer for demonstration purposes). Taking a look at the base table structure we can find a single function pointer, named print, to a function taking a pointer to a Base as its single argument.

The derived class structure contains a pointer to the virtual table containing the derived function pointers, the data members of the base class as well as the data members of the derived one. The function pointer table of the derived class on the other hand has a union containing an instance of a BaseTable structure and another function pointer named print, this time taking a pointer to a Derived structure. The DerivedTable also has another function pointer defining the readFromFile method.

In order to put this all together, let’s first take a look at the BaseConstruct method:

BaseTable baseTable;

void BasePrint(Base *_this)

{

printf("Base::print, baseMember = %d\n", _this->data.baseMember);

}

void BaseConstruct(Base *_this, int baseMember)

{

// TODO move this to static initialization code

baseTable.print = &BasePrint;

_this->vfptr = &baseTable;

_this->data.baseMember = baseMember;

}The first thing this method does is to (re)initialize a global structure instance of the BaseTable. This is the function pointer table used by all Base instances. We could initialize this once at startup time, but for the sake of simplicity we will skip this optimization and always initialize the table when constructing a new Base instance.

The second line sets the pointer to the function pointer table of the base object to the single global instance and finally the third line initializes the data member.

What do we have at the end of the base constructor? We have a global object containing function pointers to the member methods of the base class as well as a single instance of that base class whose vfptr member points to the global function pointer table and whose data member is initialized to whatever value we passed to the constructor. Seems similar to a C++ constructor, doesn’t it?

Take a look at the Derived class:

typedef struct Derived_t Derived;

typedef struct DerivedTable_t

{

union

{

BaseTable baseFunctions;

void (*print)(Derived* _this);

};

void (*readFromFile)(Derived* _this);

} DerivedTable;

typedef struct DerivedData_t

{

int derivedMember;

} DerivedData;

typedef struct Derived_t

{

DerivedTable *vfptr;

BaseData base;

DerivedData data;

} Derived;

void DerivedConstruct(Derived *_this, int baseMember, int derivedMember);

void DerivedDestroy(Derived *_this);There are a few gems in that piece of code (or germs, depending on your point of view), so let me elaborate:

The Derived table is similar to the Base table in that I has function pointers for all function that base also has, but those methods take a pointer to a derived object instead of a pointer to a Base object. Therefore, I put the BaseTable structure in a union alongside the overridden function pointers (print with a pointer to a Derived object).

Additionally, since Derived specifies another virtual function (readFromFile), I added that outside of the union. Note that the union is cosmetics only: Both table structures, BaseTable as well as DerivedTable consist only of function pointers and we could work around this using casting, but the union reduces the number of casts we need a little bit.

The rest of the Derived class is pretty straightforward: A pointer to the DerivedTable function table, the members of the Base class (BaseData) and the members of the Derived class (DerivedData).

Going further, we inspect the DerivedConstruct method:

DerivedTable derivedTable;

void DerivedPrint(Derived *_this)

{

printf("Derived::print, baseMember = %d, derivedMember = %d\n", _this->base.baseMember, _this->data.derivedMember);

}

void DerivedReadFromFile(Derived *_this)

{

printf("Derived::readFromFile");

}

void DerivedConstruct(Derived *_this, int baseMember, int derivedMember)

{

// TODO move this to static initialization code

derivedTable.print = DerivedPrint;

derivedTable.readFromFile = DerivedReadFromFile;

BaseConstruct((Base*)_this, baseMember);

_this->vfptr = &derivedTable;

_this->data.derivedMember = derivedMember;

}On its first two lines it also initializes a global structure containing function pointers to the members of the derived class. Once again, this could be moved to a global startup method, but we do this for every instance for now.

The constructor method then goes on calling the BaseConstruct method, passing the parameters it requires. After that, it updates the pointer to the function pointer table to point to the global pointer table for the Derived class. Yes, I correctly mean that it updates the pointer to the global structure, because it was already set up in the BaseConstruct method, but after we actually finished that it changes it to point to the Derived function pointer table. Note that we casted the pointer to a Base*, which works because the Base structure is smaller than the Derived structure and the function pointer is the first member.

Wow, crazy? Adding up, after calling the DerivedConstruct method we have a structure whose pointer to a function pointer table points to a global structure containing function pointers to all derived member functions (after first having pointed to the Base function pointer table) and whose data members are all initialized because the BaseConstruct method was called for the base class and the DerivedConstruct method also initialized the derived member. Seems similar to a C++ constructor calling the base constructor.

In order to see all this wonderful C stuff (unions!), take a look at the main method:

void printObject(Base *base)

{

base->vfptr->print(base);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

Base base;

Derived derived;

BaseConstruct(&base, 10);

DerivedConstruct(&derived, 10, 20);

printObject(&base);

printObject((Base*)&derived);

DerivedDestroy(&derived);

BaseDestroy(&base);

return 0;

}We create two structures on the stack, one for Base and one for Derived. First we call the BaseConstruct method with a pointer to the Base instance on the stack and some integer value. After that we call DerivedConstruct in order to initialize the Derived class.

After we have constructed the two objects we can see all the object-orientation goodness in the printObject method which calls the print function referenced in the function pointer table of the object passed in the form of a pointer.

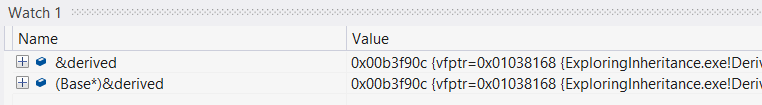

Stepping through the debugger, we find that casting from Derived to Base works, but only because we kept a close eye on the alignment in memory (especially concerning the function pointer tables):

Because function pointers are the same size, no matter what their exact signature is, we can reuse the same code we used for Base and instead have it work with a Derived instance: A key principle in object oriented programming. Note that I do this for a deeper understanding of C++ only and would never use such kind of inheritance for production code. Just to be sure.

You can find all of the code on github (here: https://github.com/paumayr/cppexamples/tree/master/BlogEntries/ExploringInheritance).

Now, if all of this seemed too obvious to you, see what happens when we get into multiple inheritance, which I covered in a separate blog post.