Exploring C++ Inheritance (2 of 2)

17 May 2013 - CPP, Visual Studio

Introduction

In the first entry discussing C++ inheritance, I covered how basic inheritance works: A hidden pointer to a virtual function pointer table is used to dispatch to the correct method. I pointed out that the addresses of the objects, no matter how I casted them around stayed the same. Now this was pretty straightforward for single inheritance, but you will see why this becomes quite special with multiple inheritance:

Scenario

I extended the scenario we had in the first blog entry with a second base class I called AnotherBase. This class has a single integer data member called anotherMember and a virtual function called scan (I somehow had two base classes, one for printers and one for scanners in mind.). Finally, we extended the Derived class to also inherit from AnotherBase and overriding the scan method as well as the print method of the respective base class (Imagine a multifunction device acting as a scanner as well as a printer).

class Base

{

protected:

int baseMember;

public:

Base(int baseMember);

~Base();

virtual void print();

};

class AnotherBase

{

protected:

int anotherBaseMember;

public:

AnotherBase(int anotherBaseMember);

~AnotherBase();

virtual void scan();

};

class Derived : public Base, public AnotherBase

{

public:

Derived(int baseMember, int anotherBaseMember);

virtual ~Derived();

virtual void readFromFile();

};The code change was pretty straight forward, so let’s take a look at what the debugger tells us if we look at the pointer values casted to different Base classes:

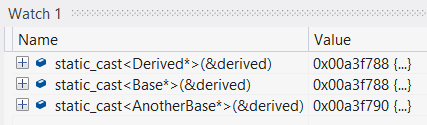

See anything fishy? Correct, the Value of the pointer casted to AnotherBase* has a different value than the other pointers. To be exact, it is off by 8 bytes, which is exactly the size of a Base (pointer to function table + base data members). Also, if we look at the size of a Derived structure we will notice that it is 16 bytes large even though we only have two integer data members. Your guess is correct, we get two pointers to two different function tables.

Theory

Now why is this? Couldn’t we just have a single pointer to the function pointer table of the class Derived? In theory, a single pointer would give us enough information as to which method we have to call at which given point in time. The problem is that the code dispatching the correct function call has to be fast and remain static, meaning that it cannot change depending on the pointer passed in: It always calls a specific function referenced by a function pointer at a specific position relative to the virtual function table pointer of the object and passes the pointer to the object as a first parameter to that function called.

The function that is called assumes that it gets a pointer to an object whose first member is a pointer to a virtual function pointer table, so when data members are referenced it adds the required offset.

Therefore, in order to have a correct representation of that structure so that it can be processed by the member function code, we have a full object with its own pointer to a virtual function table.

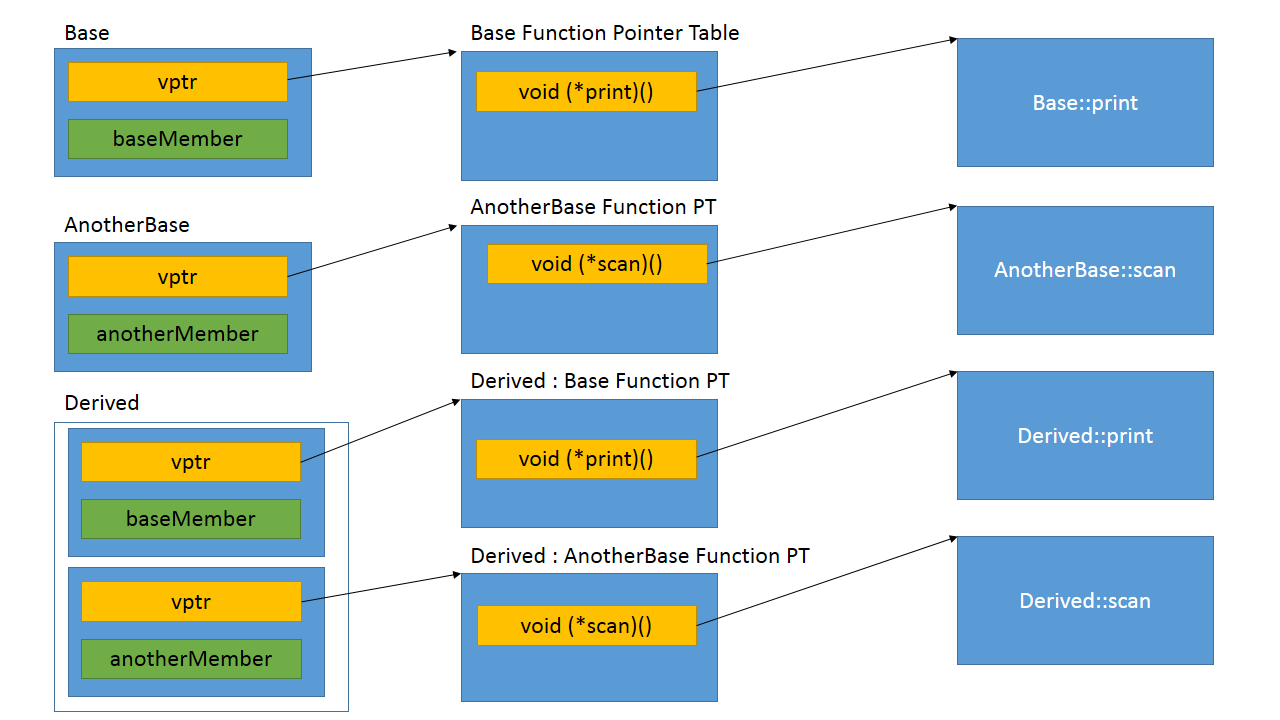

Since my textual explanations are probably somewhat hard to grasp at times, here are some visualizations (thank you power point!):

The instances (left) have pointers to the virtual function pointer tables (middle) which in turn contain pointers to the actual functions (right).

C Version

Now that we know the memory layout of those classes, can we build something similar in C? Of course we can, but it will not be pretty. For that reason, I want to add a Disclaimer here, that this code is only for demonstrating how C++ multiple inheritance works under the covers. I do not endorse writing that kind of C code (any pure C code, for that matter).

Before we dive deeper into the individual functions, here are the structures for the base classes:

typedef struct Base_t Base;

typedef struct BaseTable_t

{

void (*print)(Base *_this);

} BaseTable;

typedef struct BaseData_t

{

int baseMember;

} BaseData;

typedef struct Base_t

{

BaseTable *vfptr;

BaseData data;

} Base;

void BaseConstruct(Base *base, int baseMember);

void BaseDesturct(Base *base);

typedef struct AnotherBase_t AnotherBase;

typedef struct AnotherBaseTable_t

{

void (*scan)(AnotherBase *_this);

} AnotherBaseTable;

typedef struct AnotherBaseData_t

{

int anotherBaseMember;

} AnotherBaseData;

typedef struct AnotherBase_t

{

AnotherBaseTable *vptr;

AnotherBaseData data;

} AnotherBase;

void AnotherBaseConstruct(AnotherBase *_this, int anotherBaseMember);

void AnotherBaseDestruct(AnotherBase *_this);As you can see I separated the pointers to the tables from the data members in order to reuse some of the structures. So, for the Base class, we have a structure “BaseTable”, as before as well as a structure “BaseData” containing the base member variables and finally a structure “Base” that contains the pointer to the BaseTable as well as an instance of the data members. The structures for “AnotherBase” are similar.

Now, here is the structure for the Derived class:

typedef struct Derived_t Derived;

typedef struct DerivedTable_t

{

union

{

BaseTable baseFunctions;

void (*printBase)(Derived *_this);

};

void (*readFromFile)(Derived *_this);

} DerivedTable;

typedef struct DerivedData_t

{

int derivedMember;

} DerivedData;

typedef struct Derived_t

{

DerivedTable *vfptrDerived;

BaseData baseData;

AnotherBaseTable *vfptrAnotherBase;

AnotherBaseData anotherBaseData;

DerivedData derivedData;

} Derived;

void DerivedConstruct(Derived *derived, int baseMember, int anotherBaseMember, int derivedMember);

void DerivedDestruct(Derived *derived);If you recall the Derived structure from the last Blog entry, you will recognize a similarity, but additionally we added a pointer to an instance of “AnotherBaseTable” and an instance of the “AnotherBaseData” structure. These two members make up the representation of the “AnotherBase” class.

The constructor functions for the base classes remain the same, so let’s fast-forward to the constructor function for the derived class:

void DerivedConstruct(Derived *derived, int baseMember, int anotherBaseMember, int derivedMember)

{

// TODO move this to static initialization code

derivedTable.printBase = DerivedPrint;

derivedTable.readFromFile= DerivedReadFromFile;

derivedAnotherBaseTable.scan = DerivedScan;

BaseConstruct((Base*)derived, baseMember);

AnotherBaseConstruct((AnotherBase*)&derived->vfptrAnotherBase, anotherBaseMember);

derived->vfptrDerived = &derivedTable;

derived->vfptrAnotherBase = &derivedAnotherBaseTable;

derived->derivedData.derivedMember = derivedMember;

}As you can see, we have a global instance of DerivedTable as well as a global instance of AnotherBaseTable which I called “derivedTable” and “derivedAnotherBaseTable”. Note, that we reuse the same structure for the function pointer table as the AnotherBase class uses, but our constructor function fills it with pointers to different members. Once again, we could move this table initialization code to a function called once at startup.

The function table initialization code is followed by two calls to the constructors to the Base classes. For the Base constructor we solely need to cast the pointer to a Base pointer, but for AnotherBase the pointer is the address of the pointer of the virtual function table pointer. That is the offset we found while taking a look at the pointer addresses.

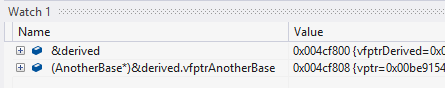

Finally both pointers to function pointer tables are set to the derived tables and the derived member is initialized. This is what the final object looks like in the watch window:

Recognize the offset of 8 bytes? That is exactly the same offset we had in the C++ version. Sounds good to me, let’s use it:

void callScan(AnotherBase *anotherBase)

{

anotherBase->vptr->scan(anotherBase);

}

void callPrint(Base *base)

{

base->vfptr->print(base);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

Base base;

AnotherBase anotherBase;

Derived derived;

BaseConstruct(&base, 10);

AnotherBaseConstruct(&anotherBase, 20);

DerivedConstruct(&derived, 30, 40, 50);

callPrint(&base);

callPrint((Base*)&derived);

callScan(&anotherBase);

callScan((AnotherBase*)&derived.vfptrAnotherBase);

return 0;

}Here we have two functions that use the two different Base classes: callScan and callPrint. In the main method we first instantiate the structures and call the corresponding constructors. We then call the callPrint method as we had done before using single inheritance only, finally to call the callScan method, we need a pointer to an instance of “AnotherBase” which is embedded in our derived class and starts at the address of the pointer to its virtual function pointer table. So we pass it the address to that pointer and cast it to a pointer to an AnotherBase. Two both function, the passed in pointer than appears to be an instance of the expected class and the will happily execute their logic.

But take a closer look at the DerivedScan method:

void DerivedScan(AnotherBase *anotherBase)

{

// we know that we are called through a derived instance -> get the pointer to the derived

const size_t offset = sizeof(BaseData) + sizeof (DerivedTable*);

Derived *_this = (Derived*)(((unsigned char*)anotherBase) - offset);

printf("Derived::scan, baseMember = %d, derivedMember = %d, anotherBaseMember = %d\n",

_this->baseData.baseMember, _this->derivedData.derivedMember, _this->anotherBaseData.anotherBaseMember);

}Remember, that the call contract for the scan method requires a pointer to an AnotherBase instance which is offset by 8 bytes into the derived structure. In order to retrieve a pointer the Derived instance we need to subtract 8 bytes from the passed in pointer and we can then access all the members of the derived instance.

Summary

Writing stuff like this for exploration is fun, but if I had to take ownership of such code in a project, I’d search for the original author and tell him that a C++ compiler does this even better. Seriously, if you want to do object oriented programming use a language that is designed to support this. Just like you would use time cockpit for time tracking instead of Excel, right ? ;).

You can find the referenced here on my public github repository: https://github.com/paumayr/cppexamples/tree/master/BlogEntries/ExploringInheritance.